Want accurate information about elections? Don’t ask an AI chatbot, experts warn — even if it seems confident of its answers and cites seemingly trustworthy sources.

New research from a pair of European nonprofits finds that Microsoft’s Bing AI chatbot, recently rebranded as Microsoft Copilot, gave inaccurate answers to 1 out of every 3 basic questions about candidates, polls, scandals and voting in a pair of recent election cycles in Germany and Switzerland. In many cases, the chatbot misquoted its sources.

The problems were not limited to Europe, with similar questions eliciting inaccurate responses about the 2024 U.S. elections as well.

The findings from the nonprofits AI Forensics and AlgorithmWatch, shared with The Washington Post ahead of their publication Friday, do not claim that misinformation from Bing influenced the elections’ outcome. But they reinforce concerns that today’s AI chatbots could contribute to confusion and misinformation around future elections as Microsoft and other tech giants race to integrate them into everyday products, including internet search.

“As generative AI becomes more widespread, this could affect one of the cornerstones of democracy: the access to reliable and transparent public information,” the researchers conclude.

As AI chatbots such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Microsoft’s Bing and Google’s Bard have boomed in popularity, their propensity to spit out false information has been well-documented. In an effort to make them more reliable, all three companies have added the ability for the tools to search the web and cite the sources for the information they provide.

But that hasn’t stopped them from making things up. Bing routinely gave answers that deviated from the information in the links it cited, said Salvatore Romano, head of research for AI Forensics.

The researchers focused on Bing, now Copilot, because it was one of the first to include sources, and because Microsoft has aggressively built it into services widely available in Europe, including Bing search, Microsoft Word and even its Windows operating system, Romano said. But that doesn’t mean the problems they found are limited to Bing, he added. Preliminary testing of the same prompts on OpenAI’s GPT-4, for instance, turned up the same kinds of inaccuracies. (They did not test Google’s Bard because it was not yet available in Europe when they began the study.)

Notably, the inaccuracies in Bing’s answers were most common when questions were asked in languages other than English, the researchers found — raising concerns that AI tools built by U.S.-based companies may perform worse abroad.

Questions asked in German elicited at least one factual error in the response 37 percent of the time, while the error rate for the same questions in English was 20 percent. Questions about the Swiss elections asked in French had a 24 percent error rate.

Safeguards built into Bing to keep it from giving offensive or inappropriate answers also appeared to be unevenly applied across the languages. It either declined to answer or gave an evasive answer to 59 percent of queries in French, compared with 39 percent in English and 35 percent in German.

The inaccuracies included giving the wrong date for elections, reporting outdated or mistaken polling numbers, listing candidates who had withdrawn from the race as leading contenders, and inventing controversies about candidates in a few cases.

In one notable example, a question about a scandal that rocked German politics ahead of the October state elections in Bavaria elicited an array of different responses, some of them false. The questions revolved around Hubert Aiwanger, the leader of the populist Free Voters party, who was reported to have distributed antisemitic leaflets as a high-schooler some 30 years ago.

Asked about the scandal involving Aiwanger, the chatbot at one point falsely claimed that he never distributed the leaflet. Another time, it appeared to mix up its controversies, reporting that the scandal involved a leaflet containing misinformation about the coronavirus.

Bing also misrepresented the scandal’s impact, the researchers found: It claimed that Aiwanger’s party had lost ground in polls following the allegations of antisemitism, when in fact it rose in the polls. The right-leaning party ended up performing above expectations in the election.

The nonprofits presented Microsoft with some preliminary findings this fall, they said, including the Aiwanger examples. After Microsoft responded, they found that Bing had begun giving correct answers to the questions about Aiwanger. Yet the chatbot persisted in giving inaccurate information to many other questions, which Romano said suggests that Microsoft is trying to fix these problems on a case-by-case basis.

“The problem is systemic, and they do not have very good tools to fix it,” Romano said.

Micr0soft said it is working to correct the problems ahead of the 2024 elections in the United States. A spokesman said voters should check the accuracy of information they get from chatbots.

“We are continuing to address issues and prepare our tools to perform to our expectations for the 2024 elections,” said Frank Shaw, Microsoft’s head of communications. “As we continue to make progress, we encourage people to use Copilot with their best judgment when viewing results. This includes verifying source materials and checking web links to learn more.”

A spokesperson for the European Commission, Johannes Barke, said the body “remains vigilant on the negative effects of online disinformation, including AI-powered disinformation,” noting that the role of online platforms in election integrity is “a top priority for enforcement” under Europe’s sweeping new Digital Services Act.

While the study focused only on elections in Germany and Switzerland, the researchers found anecdotally that Bing struggled, in both English and Spanish, with the same sorts of questions about the 2024 U.S. elections. For example, the chatbot reported that a Dec. 4 poll had President Biden leading Donald Trump 48 percent to 44 percent, linking to a story by FiveThirtyEight as its source. But clicking on the link turned up no such poll on that date.

The chatbot also gave inconsistent answers to questions about scandals involving Biden and Trump, sometimes refusing to answer and other times mixing up facts. In one instance, it misattributed a quote uttered by law professor Jonathan Turley on Fox News, claiming that the quote was from Rep. James Comer (Ky.), the Republican chair of the House Oversight Committee. (Coincidentally, ChatGPT made news this year for fabricating a scandal about Turley, citing a nonexistent Post article among its sources.)

How much of an impact, if any, inaccurate answers from Bing or other AI chatbots could actually have on elections is unclear. Bing, ChatGPT and Bard all carry disclaimers noting that they can make mistakes and encouraging users to double-check their answers. Of the three, only Bing is explicitly touted by its maker as an alternative to search — though its recent rebranding to Microsoft Copilot was intended, in part, to underscore that it’s meant to be an assistant rather than a definitive source of answers.

In a November poll, 15 percent of Americans said they’re likely to use AI to get information about the upcoming presidential election. The poll by the University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy and AP-NORC found bipartisan concern that AI tools will be used to spread election misinformation.

It isn’t entirely surprising that Bing sometimes misquotes its cited sources, said Amin Ahmad, co-founder and CEO of Vectara, a start-up based in Palo Alto, Calif., that builds AI language tools for businesses. His company’s research has found that leading AI language models sometimes produce inaccuracies even when asked to summarize a single document.

Still, Ahmad said, a 30 percent error rate on election questions was higher than he would have expected. While he’s confident that rapid improvement in AI models will soon reduce their propensity to make things up, he found the nonprofits’ findings concerning.

“When I see [polling] numbers referenced, and then I see, ‘Here’s the original story,’ I’m probably never going to click the original story,” Ahmad said. “I assume copying the number over is a simple task. So I think that’s fairly dangerous.”

Want accurate information about elections? Don’t ask an AI chatbot, experts warn — even if it seems confident of its answers and cites seemingly trustworthy sources.

New research from a pair of European nonprofits finds that Microsoft’s Bing AI chatbot, recently rebranded as Microsoft Copilot, gave inaccurate answers to 1 out of every 3 basic questions about candidates, polls, scandals and voting in a pair of recent election cycles in Germany and Switzerland. In many cases, the chatbot misquoted its sources.

The problems were not limited to Europe, with similar questions eliciting inaccurate responses about the 2024 U.S. elections as well.

The findings from the nonprofits AI Forensics and AlgorithmWatch, shared with The Washington Post ahead of their publication Friday, do not claim that misinformation from Bing influenced the elections’ outcome. But they reinforce concerns that today’s AI chatbots could contribute to confusion and misinformation around future elections as Microsoft and other tech giants race to integrate them into everyday products, including internet search.

“As generative AI becomes more widespread, this could affect one of the cornerstones of democracy: the access to reliable and transparent public information,” the researchers conclude.

As AI chatbots such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Microsoft’s Bing and Google’s Bard have boomed in popularity, their propensity to spit out false information has been well-documented. In an effort to make them more reliable, all three companies have added the ability for the tools to search the web and cite the sources for the information they provide.

But that hasn’t stopped them from making things up. Bing routinely gave answers that deviated from the information in the links it cited, said Salvatore Romano, head of research for AI Forensics.

The researchers focused on Bing, now Copilot, because it was one of the first to include sources, and because Microsoft has aggressively built it into services widely available in Europe, including Bing search, Microsoft Word and even its Windows operating system, Romano said. But that doesn’t mean the problems they found are limited to Bing, he added. Preliminary testing of the same prompts on OpenAI’s GPT-4, for instance, turned up the same kinds of inaccuracies. (They did not test Google’s Bard because it was not yet available in Europe when they began the study.)

Notably, the inaccuracies in Bing’s answers were most common when questions were asked in languages other than English, the researchers found — raising concerns that AI tools built by U.S.-based companies may perform worse abroad.

Questions asked in German elicited at least one factual error in the response 37 percent of the time, while the error rate for the same questions in English was 20 percent. Questions about the Swiss elections asked in French had a 24 percent error rate.

Safeguards built into Bing to keep it from giving offensive or inappropriate answers also appeared to be unevenly applied across the languages. It either declined to answer or gave an evasive answer to 59 percent of queries in French, compared with 39 percent in English and 35 percent in German.

The inaccuracies included giving the wrong date for elections, reporting outdated or mistaken polling numbers, listing candidates who had withdrawn from the race as leading contenders, and inventing controversies about candidates in a few cases.

In one notable example, a question about a scandal that rocked German politics ahead of the October state elections in Bavaria elicited an array of different responses, some of them false. The questions revolved around Hubert Aiwanger, the leader of the populist Free Voters party, who was reported to have distributed antisemitic leaflets as a high-schooler some 30 years ago.

Asked about the scandal involving Aiwanger, the chatbot at one point falsely claimed that he never distributed the leaflet. Another time, it appeared to mix up its controversies, reporting that the scandal involved a leaflet containing misinformation about the coronavirus.

Bing also misrepresented the scandal’s impact, the researchers found: It claimed that Aiwanger’s party had lost ground in polls following the allegations of antisemitism, when in fact it rose in the polls. The right-leaning party ended up performing above expectations in the election.

The nonprofits presented Microsoft with some preliminary findings this fall, they said, including the Aiwanger examples. After Microsoft responded, they found that Bing had begun giving correct answers to the questions about Aiwanger. Yet the chatbot persisted in giving inaccurate information to many other questions, which Romano said suggests that Microsoft is trying to fix these problems on a case-by-case basis.

“The problem is systemic, and they do not have very good tools to fix it,” Romano said.

Micr0soft said it is working to correct the problems ahead of the 2024 elections in the United States. A spokesman said voters should check the accuracy of information they get from chatbots.

“We are continuing to address issues and prepare our tools to perform to our expectations for the 2024 elections,” said Frank Shaw, Microsoft’s head of communications. “As we continue to make progress, we encourage people to use Copilot with their best judgment when viewing results. This includes verifying source materials and checking web links to learn more.”

A spokesperson for the European Commission, Johannes Barke, said the body “remains vigilant on the negative effects of online disinformation, including AI-powered disinformation,” noting that the role of online platforms in election integrity is “a top priority for enforcement” under Europe’s sweeping new Digital Services Act.

While the study focused only on elections in Germany and Switzerland, the researchers found anecdotally that Bing struggled, in both English and Spanish, with the same sorts of questions about the 2024 U.S. elections. For example, the chatbot reported that a Dec. 4 poll had President Biden leading Donald Trump 48 percent to 44 percent, linking to a story by FiveThirtyEight as its source. But clicking on the link turned up no such poll on that date.

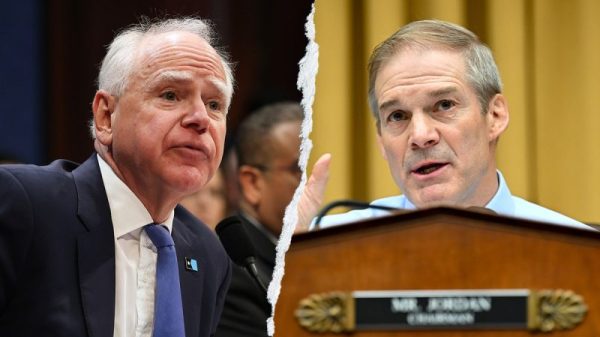

The chatbot also gave inconsistent answers to questions about scandals involving Biden and Trump, sometimes refusing to answer and other times mixing up facts. In one instance, it misattributed a quote uttered by law professor Jonathan Turley on Fox News, claiming that the quote was from Rep. James Comer (Ky.), the Republican chair of the House Oversight Committee. (Coincidentally, ChatGPT made news this year for fabricating a scandal about Turley, citing a nonexistent Post article among its sources.)

How much of an impact, if any, inaccurate answers from Bing or other AI chatbots could actually have on elections is unclear. Bing, ChatGPT and Bard all carry disclaimers noting that they can make mistakes and encouraging users to double-check their answers. Of the three, only Bing is explicitly touted by its maker as an alternative to search — though its recent rebranding to Microsoft Copilot was intended, in part, to underscore that it’s meant to be an assistant rather than a definitive source of answers.

In a November poll, 15 percent of Americans said they’re likely to use AI to get information about the upcoming presidential election. The poll by the University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy and AP-NORC found bipartisan concern that AI tools will be used to spread election misinformation.

It isn’t entirely surprising that Bing sometimes misquotes its cited sources, said Amin Ahmad, co-founder and CEO of Vectara, a start-up based in Palo Alto, Calif., that builds AI language tools for businesses. His company’s research has found that leading AI language models sometimes produce inaccuracies even when asked to summarize a single document.

Still, Ahmad said, a 30 percent error rate on election questions was higher than he would have expected. While he’s confident that rapid improvement in AI models will soon reduce their propensity to make things up, he found the nonprofits’ findings concerning.

“When I see [polling] numbers referenced, and then I see, ‘Here’s the original story,’ I’m probably never going to click the original story,” Ahmad said. “I assume copying the number over is a simple task. So I think that’s fairly dangerous.”